Not Quite Horror contains reviews of films not traditionally considered horror films. By analyzing them as horror films (identifying the monster, discussing the shared worry for the audience and the main characters, and understanding the depth of horror available to the viewer), who knows? There’s more than one way to watch a movie.

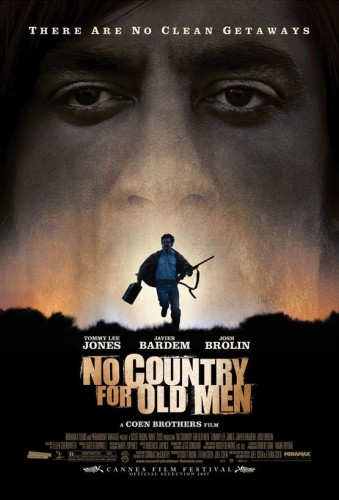

No Country for Old Men (2007)

In the month of October, I am celebrating the films of Not Quite Horror legends Joel and Ethan Coen.

The Monster: Anton Chigurh. Despite Chigurh’s awkward appearance and Javier Bardem’s masterful performance, the assassin represents a walking absence of any form of humanity. Chigurh kills efficiently and without remorse. At times he allows a coin flip to decide if a person lives or dies.

The Horror: Chigurh represents a change of pace from previously reviewed films. Perhaps owing to the Coen Brothers staying faithful to Cormac McCarthy’s source novel, the tone surrounding Chigurh lacks the sarcastic/mocking tone of many of their other films. This form of death is blank and pitiless.

The Shared Fate: Chigurgh is a perfect existential figure of dread. Everything from the nightly news to the entirety of human history contains name after name of men and women who harm others with the same lack of regard or emotion.

The Coen Brothers use this film to continue creating a body of work where death is the end, and it never ends things satisfactorily. Chigurh is another of the grim reapers, except no smile graces his face.

— I am indebted to Noel Carroll’s The Philosophy of Horror for his ideas on defining horror, as well as John Skipp and Craig Spector’s article “Death’s Rich Pageantry, or Skipp & Spector’s Handy-Dandy Splatterpunk Guide to the Horrors of Non-horror Film†in Cut! Horror Writers on Horror Film for a similar idea.–

–Axel Kohagen